Presented By: Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan

Class Education Exhibitions

Mnemonic Politics and Embodied History

During the Mao era, cultural workers in communities all over the People’s Republic of China created political exhibitions. These exhibitions were part of a larger effort to rewrite local experience, and the local landscape, in the universal language of Chinese Marxism and in the artistic style of socialist realism. Local exhibitions were one concrete form of cultural work that used tangible local detail—local speech, local diet, local forms of agriculture or industrial production—to show that local lives and local experiences conformed to the truths of Marxism, and to the universal history of the Chinese nation.

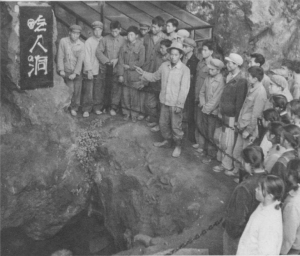

In Gejiu, a tin-mining town in southern Yunnan, cultural workers in the 1970s created an Exhibition on the History of Class Struggle in the Gejiu Tin Mines and a Recollect Bitterness Center. These joint exhibitions became the premier “classrooms” for class education in Yunnan province, instructing as many as a thousand visitors a day. During the 1950s, cultural workers in Gejiu had authenticated the local truth of Chinese Marxist history by displaying personal stories of capitalist exploitation, rags worn by miners in the inhumane “old society,” and drawings of worker uprisings. The exhibitions they created during the Cultural Revolution added historical reenactment as a new technique of political instruction. Historical reenactment primarily took the form of yiku (“recollecting bitterness”), narratives about oppression and liberation recited by the elderly. The practice of yiku invoked the older, powerful practice of suku (“venting grievances”), a method of class struggle during the land reforms of the 1940s and 1950s. Written renditions and live performances of yiku featured prominently in class education exhibitions, amplified by artwork and the display of pre-liberation artifacts. This historical reenactment enjoined visitors to “learn through experience” (tihui) the exploitation, oppression, revolt, and liberation of the Chinese proletariat. The Recollect Bitterness Center even recreated the very time and space of the narrated events. Crawling through an old mine shaft and emerging upright into the light, visitors to the Center performed the metaphorical choreography of emancipation and its structure of historical memory. This instilment of perceptual knowledge about the nature of classes and the meaning of proletarian revolution produced an embodied understanding of Chinese Marxist history, interpolated new political subjects, and incited socialist construction.

Lara Kusnetzky is a lecturer in the Department of Classical and Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at Wayne State University. She has also previously taught at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Ph.D. in Anthropology from the City University of New York (CUNY).

In Gejiu, a tin-mining town in southern Yunnan, cultural workers in the 1970s created an Exhibition on the History of Class Struggle in the Gejiu Tin Mines and a Recollect Bitterness Center. These joint exhibitions became the premier “classrooms” for class education in Yunnan province, instructing as many as a thousand visitors a day. During the 1950s, cultural workers in Gejiu had authenticated the local truth of Chinese Marxist history by displaying personal stories of capitalist exploitation, rags worn by miners in the inhumane “old society,” and drawings of worker uprisings. The exhibitions they created during the Cultural Revolution added historical reenactment as a new technique of political instruction. Historical reenactment primarily took the form of yiku (“recollecting bitterness”), narratives about oppression and liberation recited by the elderly. The practice of yiku invoked the older, powerful practice of suku (“venting grievances”), a method of class struggle during the land reforms of the 1940s and 1950s. Written renditions and live performances of yiku featured prominently in class education exhibitions, amplified by artwork and the display of pre-liberation artifacts. This historical reenactment enjoined visitors to “learn through experience” (tihui) the exploitation, oppression, revolt, and liberation of the Chinese proletariat. The Recollect Bitterness Center even recreated the very time and space of the narrated events. Crawling through an old mine shaft and emerging upright into the light, visitors to the Center performed the metaphorical choreography of emancipation and its structure of historical memory. This instilment of perceptual knowledge about the nature of classes and the meaning of proletarian revolution produced an embodied understanding of Chinese Marxist history, interpolated new political subjects, and incited socialist construction.

Lara Kusnetzky is a lecturer in the Department of Classical and Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at Wayne State University. She has also previously taught at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Ph.D. in Anthropology from the City University of New York (CUNY).